So, you want a front row seat to how a product gets developed without the constant need for a re-write every 10 days or so. Welp, you’re in the right place.

This article is an explanation of methods I’ve used to design code and systems such that you maximize test-ability, velocity and reduce technical debt throughout the life of the product. This article represents a culmination of experience building and scaling products at https://mailgun.com.

So, we are going to follow an imaginary product from design, to deployment, to scale and unforeseen new requirements. We are glossing over a TON of detail and will jump around a bit, with the goal giving you a birds eye view of how good code architecture can become an asset over the life of a product.

Ready? Let’s do this….

Mental Models

Let’s start by thinking about how we should mentally model our code architecture. A mental model allows us to reason about the system as a whole without having to understand all the details of the abstractions that make up the mental model. The mental model I’m presenting here has successfully been used to create and reason about code and architecture at Mailgun. This way of thinking presents us with maximum flexibility, helps us avoid and manage technical debt, and allows us to maintain high-quality code over the lifetime of the product.

In this article we present an approach inspired by Problem Domains, Abstraction, Separation Of Concerns and Data Ownership principles. Most of these principles are not new and have been around for years. Mastering these concepts are vitally important to writing good code, and good architecture.

What is good code?

Good Code is easy to change code. Good Architecture is easy to change Architecture. Thus your goal is to design systems which make change easy within your problem domain.

Let’s consider the creation of an email forwarding product, and for the remainder of this article we will follow this product throughout its creation and maintenance life cycle to see how the movement of data, interfaces, and code change can play out over the life cycle of a product.

The Forwarding Product

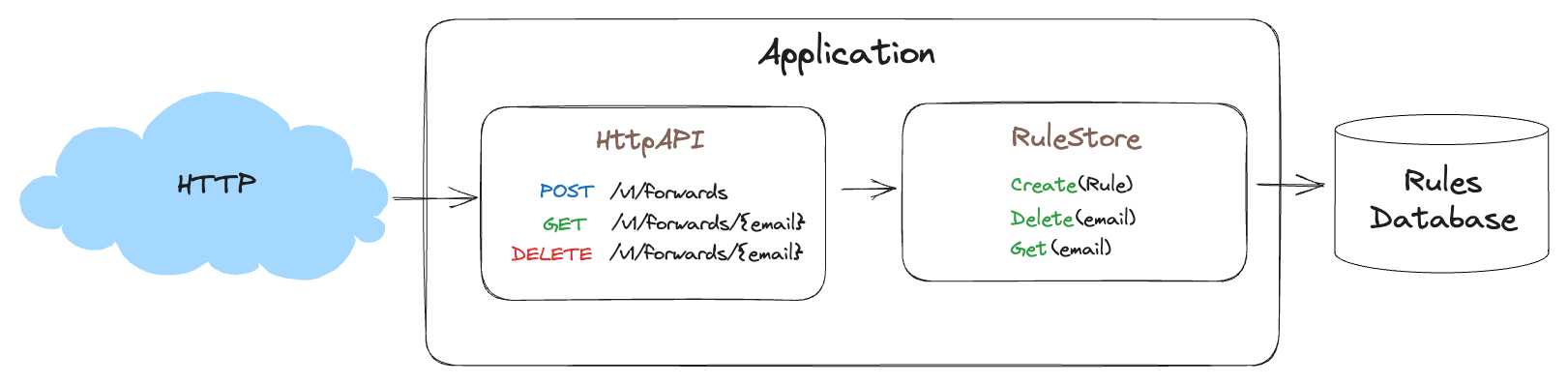

Let us first consider a simple CRUD interface for our product. This is where users will create and delete forwarding rules for our email forwarding product.

POST /v1/forwards

{

"email": "from@example.com",

"forward": "forward@email.com"

}

GET /v1/forwards{email}

DELETE /v1/forwards{email}Here we define the simplest of features for our product. With this, we can create a rule that says. “When we receive an email addressed to from@example.com we forward the the email to forward@email.com”

Now let’s assume we will store these rules in a database and model the interfaces that will make up this portion of our service.

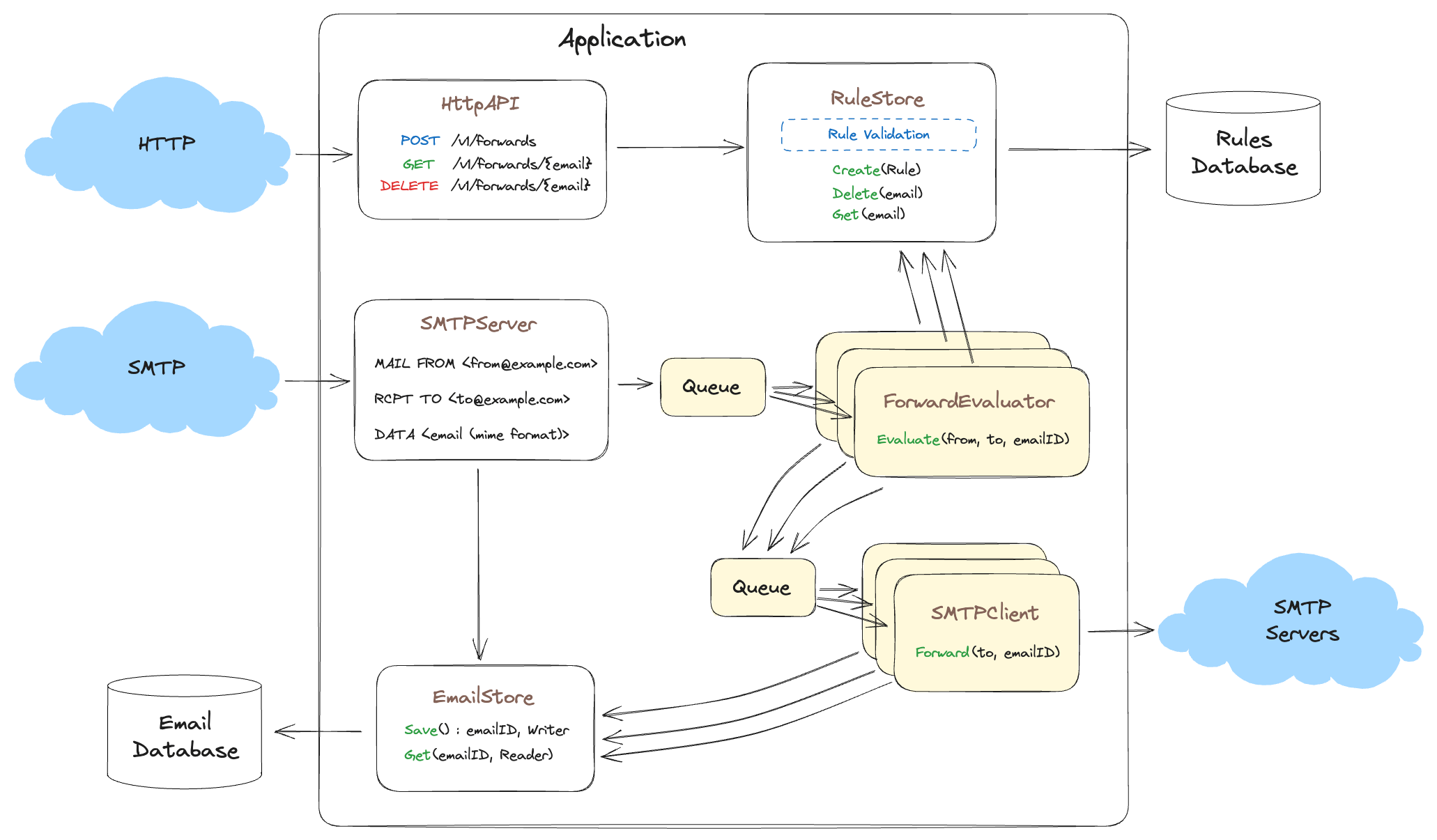

The first two interfaces in our mental model are also abstractions of both input and output. The RuleStore abstracts away the database we are using and is an example of the Repository pattern. The second abstraction is the HttpAPI. You can think of HttpAPI not as the interface for the service, but as a network interface for the RuleStore. This is because it’s primary function is to expose RuleStore methods to the network.

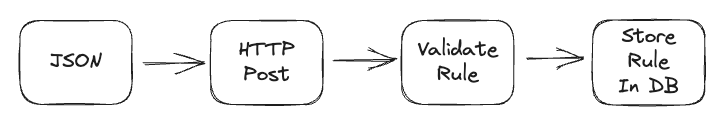

But why don’t we just organize the code in a procedural manner? These interfaces don’t seem to follow the procedure of what is actually happening to the data as it passes through the service, why would we complicate things with interfaces so early in the project? To understand why these abstractions are SO important, let’s talk about how the rule (our data) passes through our system from a strictly procedural point of view. Here is a visualization of what is occurring when we create a new rule.

In the Procedural model, the user creates a JSON rule in accordance with our API and sends it via HTTP Post. We then validate the rule (aka, are the email addresses valid?) and then we store it in a database.

You may reason that when the HttpAPI handler receives the JSON rule, it should un-marshal it into a struct and then validate the rule before saving it in the database, and all of the code can live in the handler. Why would we litter this seemingly simple operation across two different interfaces and multiple methods?

This procedural logic might even seem intuitive, if you think of the HttpAPI handler as the gatekeeper protecting the rest of the service from bad data. But here I want to introduce the second major concept to think about when constructing your mental models.

Data Ownership

We should ask ourselves, who is responsible for the rules having the correct data? Who owns the rules? Who protects the rules and the database from abuse? This line of questioning is important to the mental model, because if we identify who owns what, we can consolidate validation and protect our data in one place and simplify our mental model. If we have no clear ownership, then validation and data protection code can become spread across many different parts of the code base and may be forgotten as the product grows and new features added and subtle bugs introduced. This idea of ownership works well with the Repository pattern as you can think of the Repository as owning the Rule while at rest (saved in a database). It also works well with pipelines, where ownership of an aspect of the data can transfer from one abstraction to another, such as when the data is transformed. Once the data has been transformed, ownership of the transformed data could be passed to a different module in the system.

However, one might reason that the HttpAPI interface should own the data as it takes ownership of the data from the network, since the data is transformed from a serialization format to in code structure. But, the data only passes through HttpAPI on it’s way to the RuleStore. In a way, the HttpAPI is just a transformer of the data. The only concern of HttpAPI is getting the data from HTTP via JSON and transforming it into a structure that RuleStore understands. You can think of HttpAPI as essentially a network adapter that allows access to the RuleStore via the HTTP protocol. Thinking in this way, we see that while both HttpAPI and RuleStore abstract input and output for the entire service, they can also be abstractions for internal modules. Building our code around these abstractions can become quite useful in the future as new capabilities to the API are added.

WHY tho? KISS (Keep It Simple Stupid) tells us to do the simplest thing that works, in that case we should just unmarshall the JSON, validate it and store it in the database all in the HTTP handler for /v1/forwards. What is all of this interface and ownership garbage?

By way of explanation, let us continue with the life cycle of the forward project to see how these interfaces/abstractions benefit us in the long run.

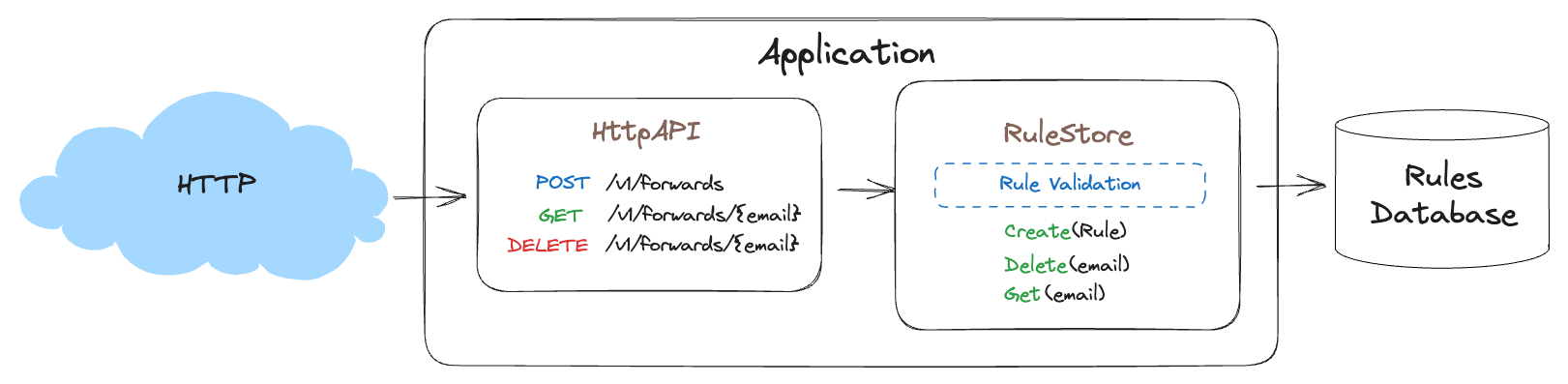

Returning to our product design, Since we have established that RuleStore owns the rules, it should also validate the rules before storing them in the database. We say that RuleStore is “protecting” the database from bad or incomplete data by validating the data given for storage. Let’s update the diagram to reflect that ownership.

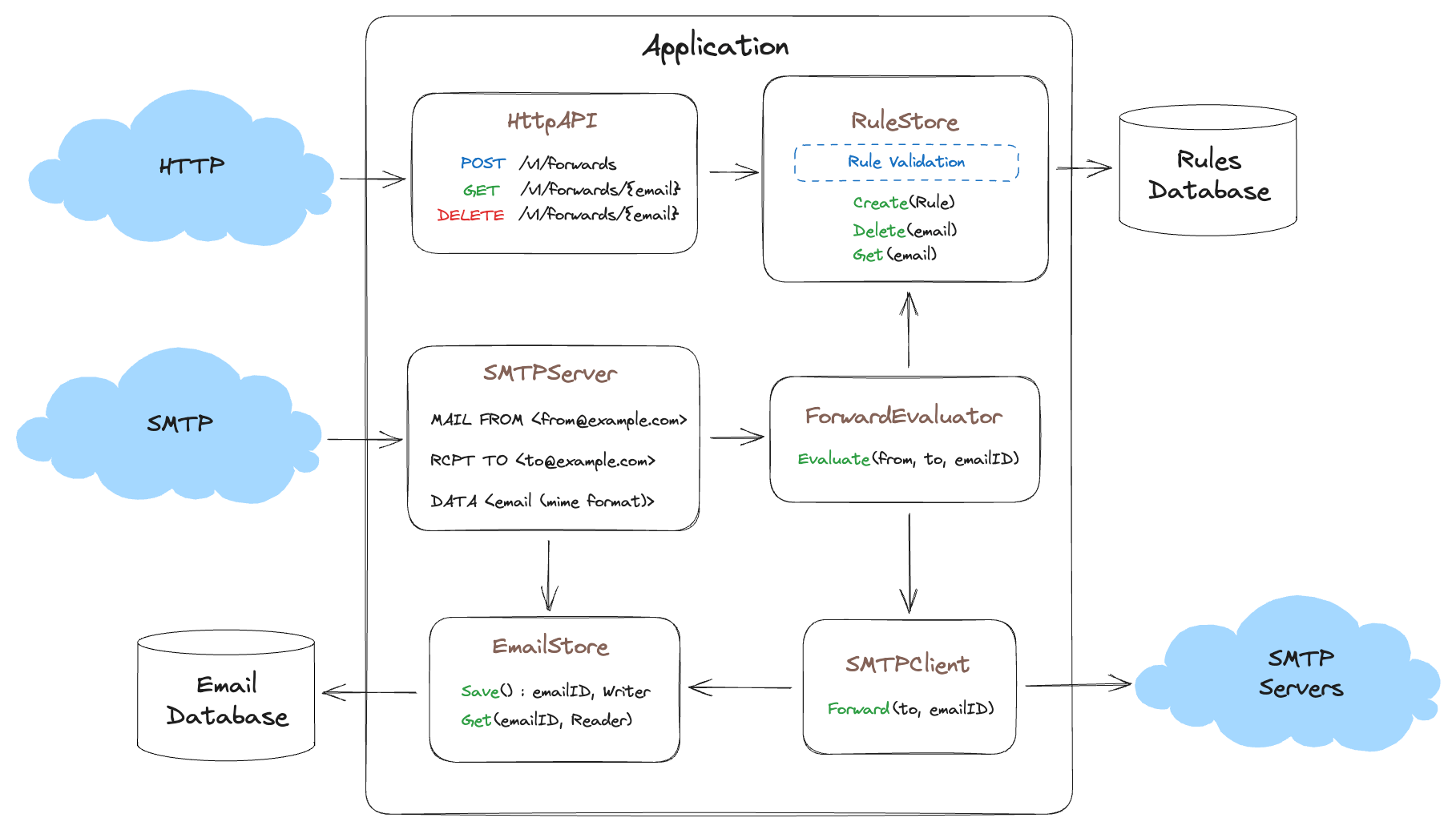

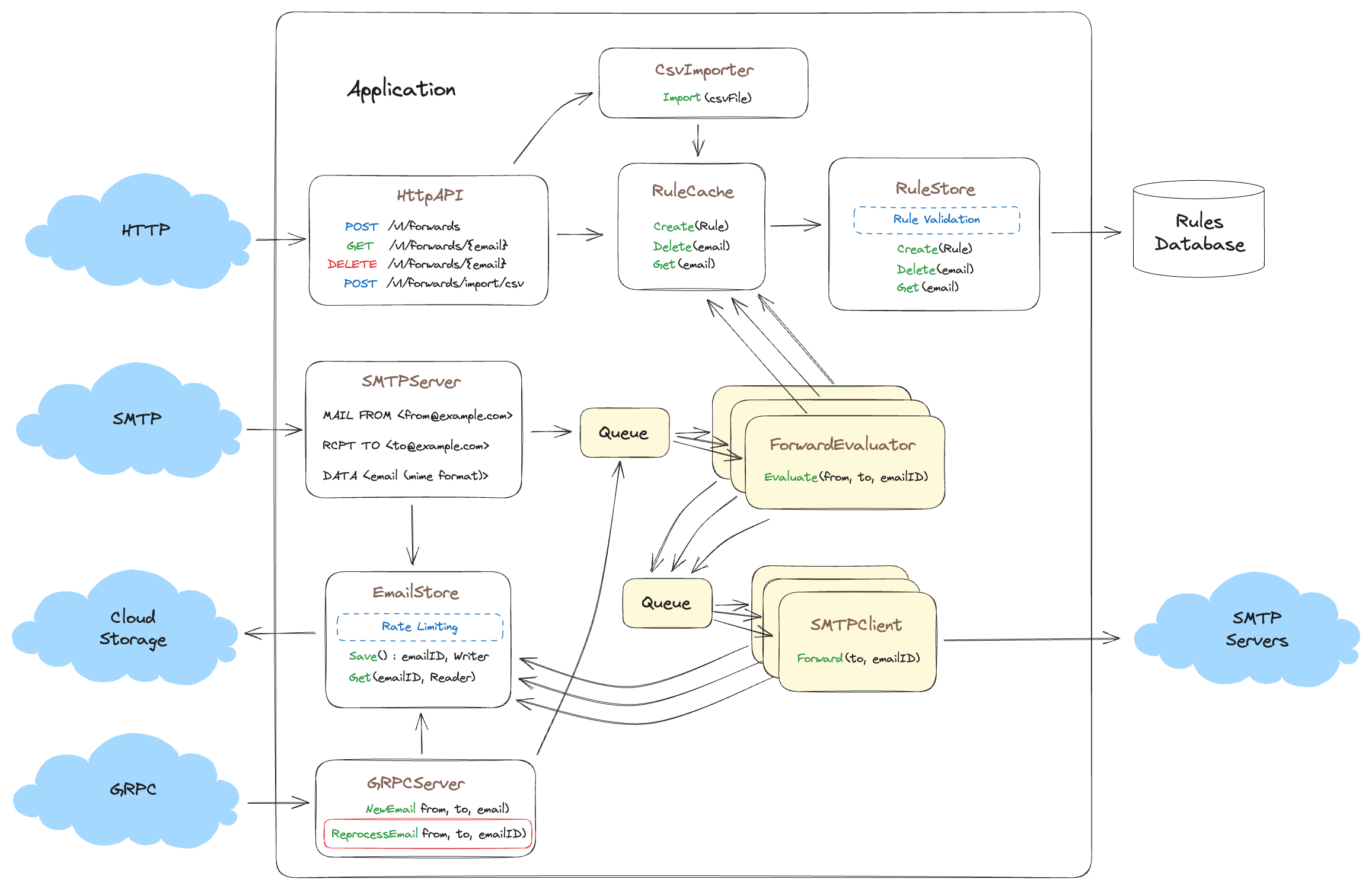

The next major part of our product is giving our customers an interface through which they will send us emails to be forwarded. We need an SMTP server we will use to receive emails, store them and forward emails that match our rules. Let’s diagram what this might look like.

Note

Some of these diagram images are quite large. You can make the images larger by simply using your browsers ZOOM feature

CMD +on OSX andCTRL +on Windows.

Here again we abstract our application input with SmtpServer which stores the email (in the form of a MIME) in the EmailStore. Next we have the ForwardEvaluator that decides if the email matches any of the email forward rules found in the RuleStore, if it does then it uses the output abstraction SmtpClient to send the email using the EmailStore to retrieve the stored email and send it to the destination SMTP server.

The Data

We have two primary forms of data for our product, the Rule and the Email. The Rule provides the transformation criteria and the Email is the thing we are transforming. We say transforming since we are changing the To address in the MIME, and if we are good email citizen, we add a Received header before forwarding the Email to the appropriate SMTP server.

When we receive the Email via SMTP we get a To and a From which are provided via the SMTP protocol, then we receive the body or the MIME of the email. We pass the MIME; which could be many megabytes of data, to the EmailStore to be persisted to the Email Database. The EmailStore then generates an emailID which is later used to retrieve the email from the EmailStore.

When the SMTPServer receives an email, it receives the body of the email (MIME) and some metadata about the email, like who its from, and who it’s addressed too. We represent that data in the following structure.

EmailMetadata:

to: forwarded@example.com

from: from@example.com

emailID: 1234This metadata structure is what gets passed to the ForwardEvaluator in order to determine if the email matches a rule in the database.

Product Launch

At this point we have a minimal but complete email forwarding product. We launch the product, our customers are happy and we smoke brisket to celebrate. (I live in Texas, it’s what we do)

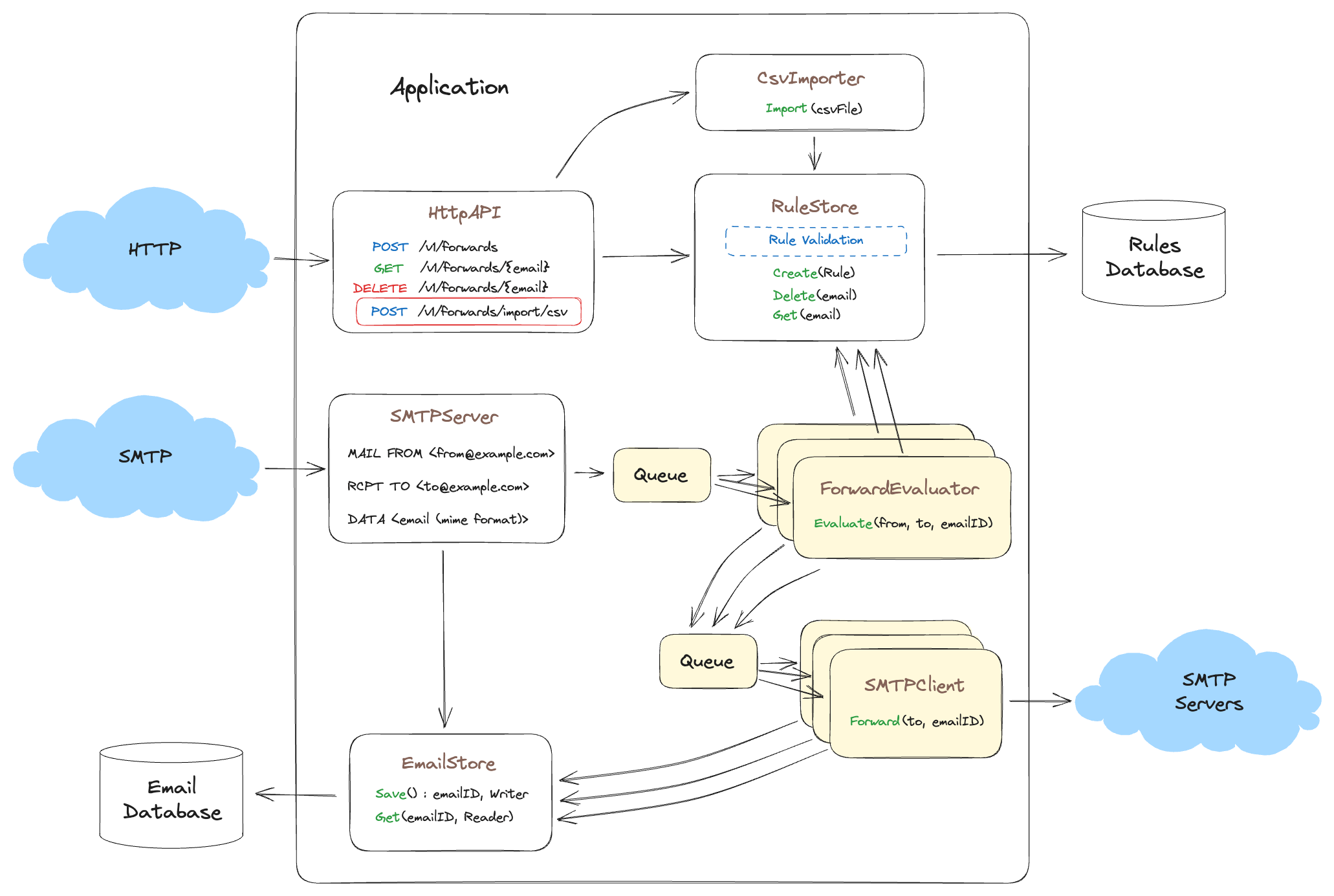

Soon after launching we notice the rule matching and forwarding is slowing down our ability to receive new email messages. We need to horizontally scale both rule processing and SMTP forwarding to keep up. Let’s implement two thread pools, the first is a pool of ForwardEvaluator threads which can process rules in parallel. Next we create a thread pool of SmtpClients to handle delivery of the messages.

Note

The

HttpAPIandSMTPServerare both multi-threaded as they must accept concurrent connections, but I omit that in this diagram for simplicity.

As you can see we use a queue (a channel in golang) to queue up work for the worker pools. The ForwardEvaluator pool takes a EmailMetadata as input (contains the from and to headers used to match the forward email address), then if a match occurs the ForwardEvaluator calls Queue(SmtpJob) for delivery via workers in the SmtpClient worker pool.

Of interest is how little actual code changed to accomplish this, most of the code is additive since we already had interfaces around each problem domain. All we did was put the interfaces into worker pools and now we can scale up to as many CPUs as the server permits. But let’s continue, and see how these interfaces continue to assist us as our product grows.

By choosing abstractions around our input, outputs, and problem domains we avoid huge and painful refactoring efforts. In addition, our mental model remains simple enough to hold inside our little grey cells.

Now… 6 months later we are signing up bigger and bigger customers. Some customers have 60,000 to 100,000 email addresses to forward. And our less tech savvy customers are asking to import these email addresses via bulk import. So we decide to add a CSV upload endpoint

Lets update our model to see how this fits in with our current design.

Here we see that not much has changed with the core product, and since validation occurs in the RuleStore there is no validation code to duplicate in CsvImporter— See how that works?

We are simply adding a new input abstraction which handles CSV imports via HTTP. Because we correctly identified ownership and input/output interfaces early, this new functionality change requires no refactoring of the current code, only the addition of a new abstraction for a new problem domain and a new handler in HttpAPI.

Here we see ownership at work. The CsvImporter takes ownership of the CSV file (the data) when it is uploaded, and transforms that CSV file into rules which are then stored in the RuleStore. This is data flowing through the system, being transformed, and data ownership being transferred after transformation of the data has occurred. Each of those ownership transfers and transformations is a separate problem domain such that we are not over loading a single problem domain with several transformations.

If you want to use the analogy of a assembly line, each transformation is a station along the assembly line where each station adds or changes something about the car (or in our case, the data) before moving along to the next station on the assembly line. In this way, we simplify our Cognitive_load and the code along with it.

Growing Pains

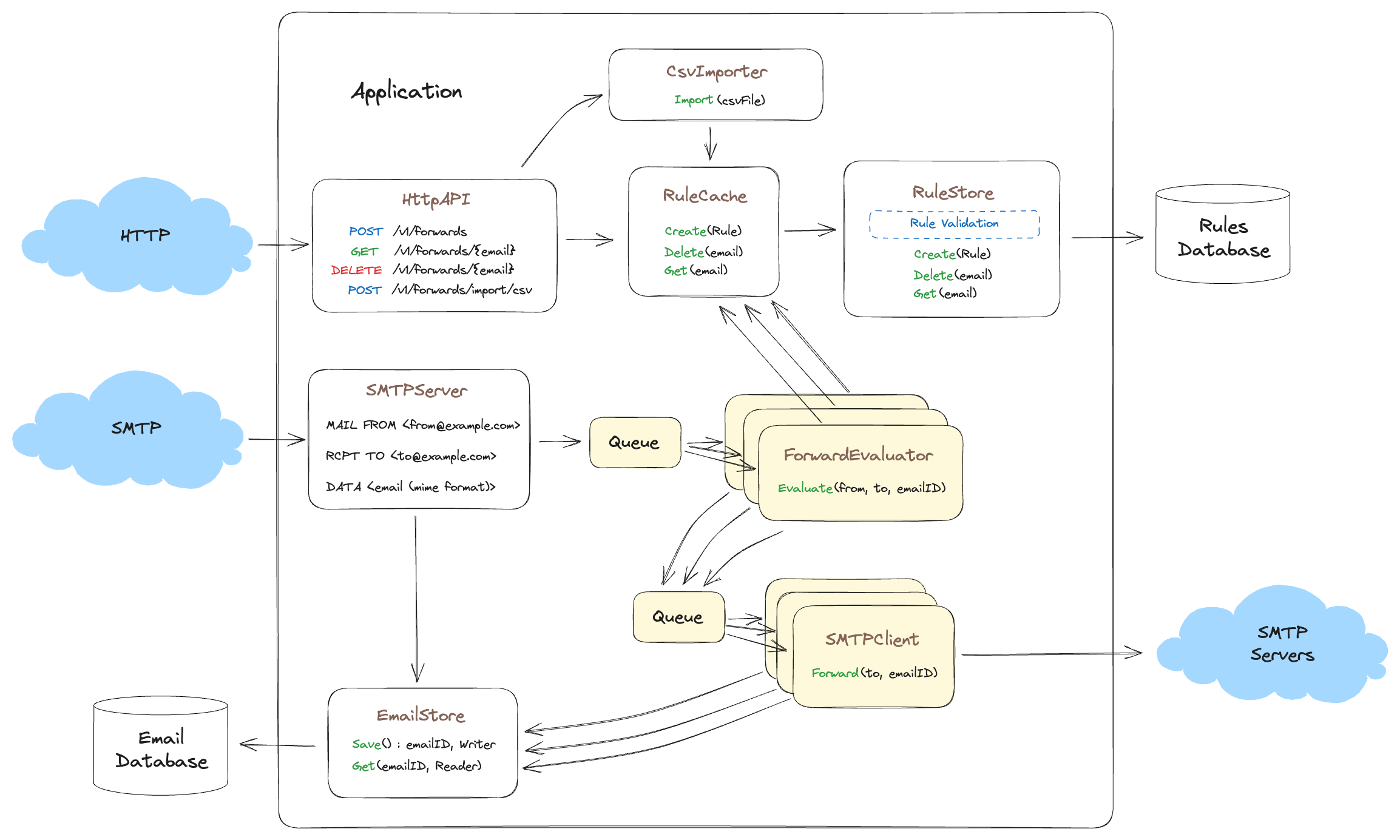

With the new addition of the CSV import, and bigger customers on boarding, our forwarding product is starting to feel the strain of success. Processing times are up and we need to improve performance if we want to continue to scale. Our metrics show the RulesStore is taking a beating from both the HttpAPI and the ForwardEvaluator looking for rules to match. It’s time to add a cache, but where to put it? Following our data ownership mental model the cache belongs with the rule store as the RuleStore owns and protects the data and the database. Additionally the RuleStore abstraction knows when to invalidate the cache as rules are deleted or updated and both the HttpAPI and ForwardEvaluator can take advantage of the performance improvements the cache provides without having to know of or access the cache directly.

Here we’ve abstracted away the RuleStore interface and replaced it with a cache which sits in front of the RuleStore. While it’s completely valid to encapsulate the cache inside the RuleStore, implementing it this way has some advantages. First, this separation allows us to change the cache implementation from in-memory cache to memcached or redis without requiring code changes to the RuleStore. Second, it also allows you to do really specialized things like use Groupcache to farm out cache requests to other instances of your application and have them perform RuleStore operations, thus avoiding the thundering herd problem. See this Groupcache Blog Post Third, the separation of cache code and database code allows us to change either without affecting the other.

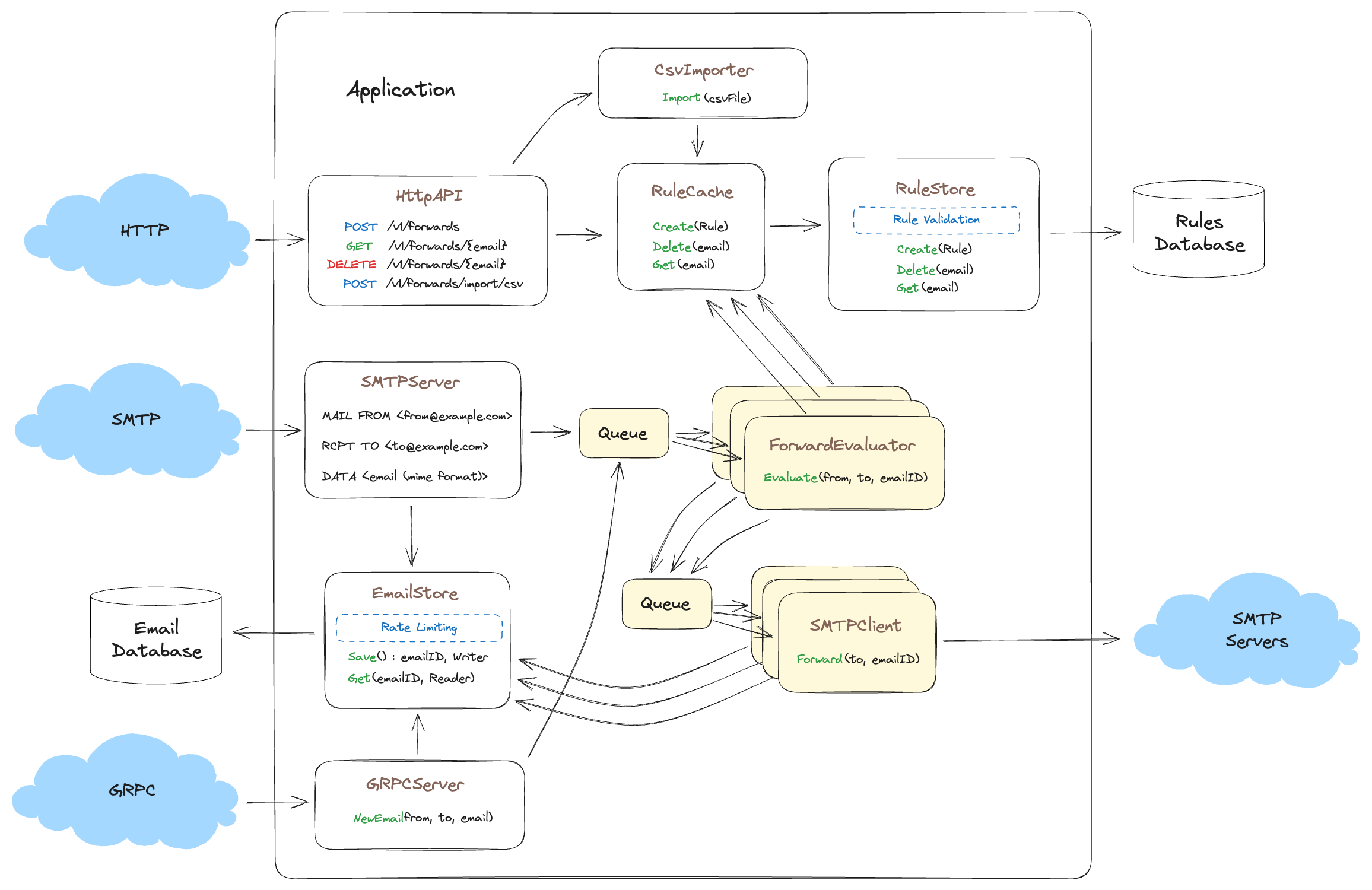

But now we’ve noticed another problem, some of our customers or random nefarious individuals on the internet have taken to abusing our SMTP server! They are sending us hundreds of megabytes of data a second, which is overwhelming our EmailStore. We need a way to protect the EmailStore from abuse! Typical wisdom might say we should limit the number of bytes customers can send us via the SMTP server. But if we think of this from a data ownership perspective, the EmailStore owns the data, shouldn’t it also protect the data from abuse? The SMTP server can and should slow down data transfer, but it does this only when the EmailStore indicates it’s being overwhelmed. The decision to rate-limit data transfer should come from the EmailStore, not the interface (in this case SmtpServer) that abstracts the EmailStore from the network. If you are still puzzled by this decision, keep reading, things should eventually become clear.

A naive implementation of the

SmtpServermight load the entire contents of the received email into memory. In this case, it might make sense to protect theSmtpServerfrom running out of memory as receiving hundreds of emails at 50mb each could quickly drain the server of all available memory. However, a better solution is to always stream large data sets in chunks via anIOReaderor similar to avoid such problems.

The price of Success

Now that our product is so successful we are being acquired by a larger email processing company! However, our new parent company has settled on GRPC for all their internal inter service communication and they want our forwarding product to support emails from both our SMTP server and emails from their SMTP servers. The catch is, their SMTP servers are going to send us emails via GRPC!?!?! Let’s see how all this changes our mental model again.

As you can see we now accept emails via both SMTP and GRPC, both interfaces benefit from the rate limiting we implemented in the EmailStore such that if both interfaces are receiving tons of emails, the EmailStore can still protect its database from getting pushed over. Additionally, we can add metrics to the EmailStore and get an accurate idea of when we need to scale our data storage.

Another often overlooked benefit to protecting our database is from internal abuse in addition to external abuse. Years ago I worked on a system that was using an ORM in Python. As such it’s often hard to decipher if the object you are interacting with is an in memory object or represents a table in a database. So while implementing a new feature I gleefully iterated over all the items in this object without realizing that the object was an ORM object that was sending N+1 selects to the database. The feature performed perfectly in tests, ran well in staging, but as soon as it was deployed it took down the production database.

If the production database had protections against abuses of this sort then we would have merely experienced an application performance degradation instead of an unexpected database outage.

Switching Databases

Speaking of overloaded databases, since integrating with our parent company SMTP servers, the number of emails being stored in the EmailStore has nearly doubled and our old database is feeling the strain. Thankfully our new parent company has negotiated a really good deal with a cloud provider’s cloud file storage product and they want us to store emails there. Since we have a nice EmailStore interface, we can switch from storing and retrieving emails from our database to the new file storage product.

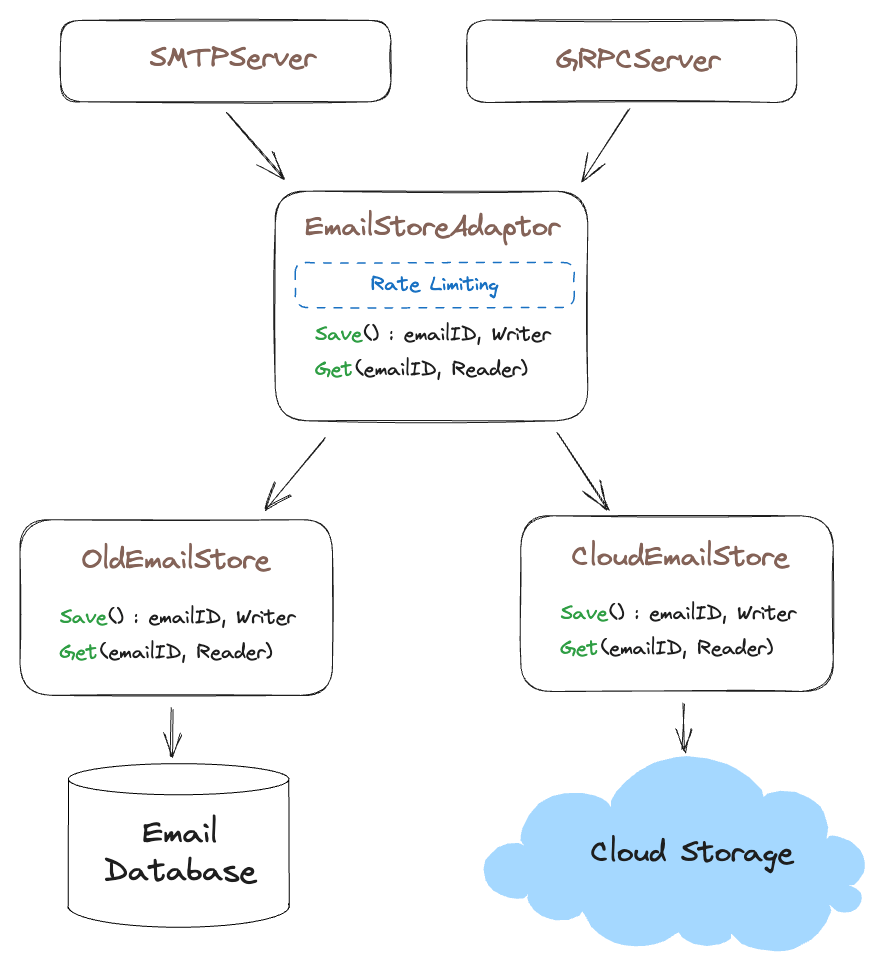

But hold on, how do we migrate all those emails from the old db to cloud storage. That’s A LOT of DATA, some of those emails are 20-50mb in size! In addition our customers expect our service to accept emails during the entire migration! To solve this, we implement a CloudEmailStore with the EmailStore interface and rename the old EmailStore to OldEmailStore. Now we create an adapter that implements the same interface called EmailStoreAdaptor which calls the OldEmailStore when it is looking for old emails and calls CloudEmailStore when storing new emails. We then build an out of band migration process to mark emails as “migrated” in the OldEmailStore database which can then inform the EmailStoreAdaptor interface that the email has already been migrated to the CloudEmailStore and it should look there instead.

Once the migration is complete, we remove the EmailStoreMigration adapter and CloudEmailStore implementation becomes the new EmailStore.

This is an important point to emphasize, we only benefit from the interface and adapter patterns here because when we originally designed the system, we abstracted away the implementation from the EmailStore interface. If we had not identified data ownership early on, this change would have been a much more complex and painful.

The Miracle Worker

Uh oh…. Looks like a routine maintenance change introduced a bug into the ForwardEvaluator. As a result, we didn’t forward any emails over the last 24 hours!

But all is not lost, thanks to a decent audit log from the SmtpServer we know all the emailID for emails we received that day. Since we abstracted our ForwardEvaluator and EmailStore from the rest of the system, we can quickly write up a new GRPC method called ReprocessEmail() to use as input for our ForwardEvaluator and reprocess all the email ids we received that day. This works because the SMTPServer stored all the received emails in the EmailStore. This combined with an audit log of all the email ids we received in the last 24 hours we can reprocess and deliver all the emails received! This looks something like this.

Now all we need is to write an out of band process to read email ids from our audit log and make a GRPC call to ReprocessEmail() for each email received that day and have it evaluated for possible forwarding; Crisis averted!

No need to hack together database queries, or wire up a one time un-tested code bit of code to preform all the processing. Instead we are using all of the existing code as is. We benefit from well defined abstractions organized by problem domain, which are thoroughly understood and tested through production use. The only new code we wrote to make this happen was in the GRPC method ReprocessEmail() and the script used to read the audit log and make calls to ReprocessEmail().

We gain a great deal of confidence our re-processing strategy will work through the re-use of existing interfaces. This would not be possible if we had applied KISS principles at the start and not taking the time to define domain driven interfaces, separated concerns, and assigned data ownership throughout our system. Congratulations, you now carry the title of “miracle worker” at the office; you’re welcome.

Introducing new Versions

Next, we will talk about introducing a new version of the forwarding product. But, as this post is already much longer than I originally planned, I’m breaking it up into separate posts. You can find the next post here Forwarding Product V2